After a four-year break, El Niño is back, leaving many to wonder what it means for California’s upcoming winter.

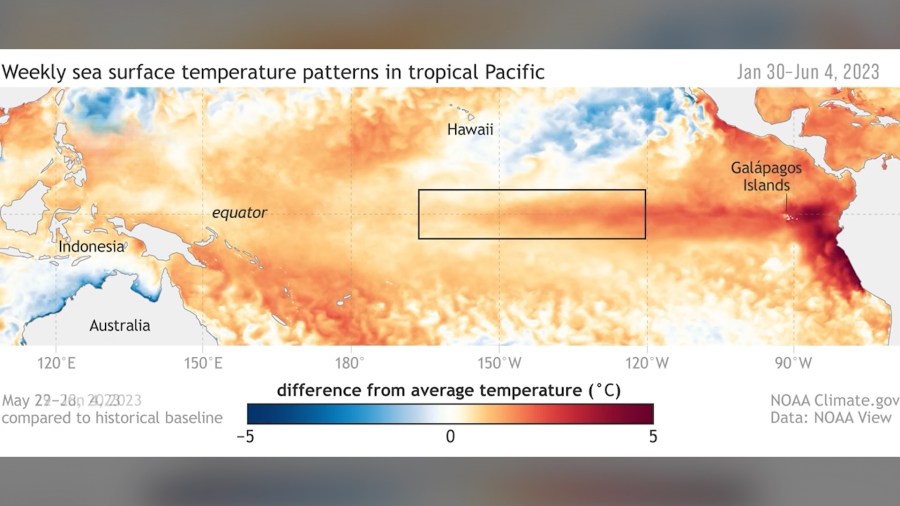

El Niño is the temporary warming of the eastern Pacific Ocean near the equator. When the water temperature rises a half-degree Celsius above normal over a three-month period, that is considered to be an El Niño pattern.

When the water rises 1.5 degrees Celsius above normal, that’s considered a strong El Niño – which may be the case this winter.

“It does appear as though this event is going to come pretty close to that if not exceed that,” said Ben Reppert, a meteorology professor at Penn State University. “If it does, it will be in the rare category along the lines of the El Niño of 2015-16 and the El Niño of [winter] 1998.”

In December 1997, 7 inches of rain fell in parts of Orange County in one day. February 1998 brought more than 13 inches of rain to downtown Los Angeles, causing major damage.

During strong El Niño winters, we typically see heavy rainfall in the southwestern United States and in Southern California. Historically, we see more snowfall in the Sierra and southern Rockies, but less snow in the Northeast.

But before you book your winter ski vacation, remember that El Niño isn’t a guarantee.

Last winter’s record snowfall in Southern California was during a La Niña when odds favored a drier winter.

“I would put my money on a relatively wet winter in Southern California. But we really can’t rule out any possible outcomes. So what El Niño really is doing is tilting the odds,” Reppert said.

Robbie Monroe with the National Weather Service believes this El Niño could create a confluence of factors that lead to flooding and mudslides.

“With potentially warmer air coming in from the Pacific, we could have higher snow levels – 10,000 feet or higher at times. And so all that water, instead of being locked up at the high elevations in the form of snow, could be coming down at the same time that we’re seeing heavier rain at lower elevations.”

While the El Niño and La Niña oscillation has a major impact on weather patterns worldwide, experts say they are naturally occurring phenomena and not inherently caused by climate change. But the frequency of these events, Reppert says, is likely linked to global warming.

“They are related to climate change in the sense that we believe that we are more likely to see more extreme El Niño and La Niña events more frequently in a warming climate,” he says.