Marine life seen swimming in unusual places. Water temperatures warmer than they should be. No snow where there should be feet of it.

Some scientists are saying “The Blob” could be playing a factor.

As monikers go, the blob doesn’t sound very worrisome.

But if you’re a salmon fisherman in Washington or a California resident hoping to see the end of the drought, the blob could become an enemy of top concern.

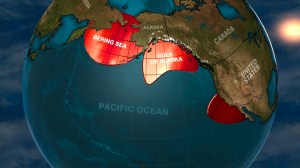

A University of Washington climate scientist and his associates have been studying the blob — a huge area of unusually warm water in the Pacific — for months.

“In the fall of 2013 and early 2014 we started to notice a big, almost circular mass of water that just didn’t cool off as much as it usually did, so by spring of 2014 it was warmer than we had ever seen it for that time of year,” said Nick Bond, who works at the Joint Institute for the Study of the Atmosphere and Ocean in Seattle, Washington.

Bond, who gave the blob its name, said it was 1,000 miles long, 1,000 miles wide and 100 yards deep in 2014 — and it has grown this year.

And it’s not the only one; there are two others that emerged in 2014, Nate Mantua of the Southwest Fisheries Science Center — part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) — said in September. One is in the Bering Sea and the other is off the coast of Southern California.

Waters in the blob have been warmer by about 5.5 degrees, a significant rise.

Persistent pressure

A recent set of studies published in Geophysical Research Letters by Bond’s group points to a high-pressure ridge over the West Coast that has calmed ocean waters for two winters. The result was more heat staying in the water because storms didn’t kick up and help cool the surface water.

“The warmer temperatures we see now aren’t due to more heating, but less winter cooling,” a recent news release from the University of Washington announcing the studies said. The university has worked with NOAA on the research.

According to New Scientist magazine, some marine species are exploring the warmer waters, leading some fish to migrate hundreds of miles from their normal habitats.

The magazine cited fisherman and wildlife officials in Alaska who have seen skipjack tuna and thresher sharks.

Pygmy killer whales have been spotted off the coast of Washington.

“I’ve never seen some of these species here before,” Bill Peterson of the Northwest Fisheries Science Center in Seattle told the New Scientist.

And he was worried about the adult Pacific salmon that normally feed on tiny crustaceans and other food sources that are not around in the same numbers off the coast of the Pacific Northwest.

“They had nothing to eat,” he told the magazine of last year’s conditions in the blob. It appears that food has moved to cooler waters.

In January, Bond told the Chinook Observer in Long Beach, Washington, that his concern is for very young salmon that are still upstream.

“In particular, the year class that would be going to sea next spring,” he said.

NOAA said in a news release last month that California sea lion pups have been found extremely underweight and dying, possibly because of an ocean with fewer things to eat.

“We have been seeing emaciated or dehydrated sea lions show up on beaches,” Justin Greenman, assistant stranding coordinator for NOAA on the West Coast, told CNN.

The numbers are overwhelming facilities that care for the stranded sea lions, most of whom are pups, local officials said.

Warmer water, less snow

The blob also is affecting life on land. For the past few years, that persistent ridge of high pressure has kept the West dry and warm, exacerbating the drought in California, Oregon and Washington.

One of the primary problems is small snow accumulation in the mountains.

In early April, officials measured the snowpack in California at a time when it should be the highest. This year it hit an all-time low at 1.4 inches of water content in the snow, just 5% of the annual average. The previous low for April 1 had been 25% in 1977 and 2014.

Gov. Jerry Brown, in announcing water restrictions the same day, stood on a patch of dry, brown grass in the Sierra Nevada mountains that is usually blanketed by up to 5 feet of snow.

The heat has caused rising air, which can lead to conditions that produce more thunderstorms. With warmer air in California, areas at higher elevations that usually see snow have seen rain instead. That has led to the lower snowpack and helped compound the drought. The storms also mean more lightning and more wildfires.

And the blob affects people on other areas of the country.

That same persistent jet stream pattern has allowed cold air to spill into much of the Midwest and East.

This stuck pattern has led to the record cold and snow in the Midwest and Northeast over the last two seasons with record snows we have seen in Boston and Detroit, and the most snow we have seen in decades for cities such as Chicago.

Still a mystery

The weather pattern is confusing the experts.

There are some that think it might be a Pacific Decadal Oscillation, a long-lasting El Nino-like pattern in the Pacific.

Dennis Hartmann, a professor of atmospheric science at the University of Washington, doesn’t believe the answer is clear.

“I don’t think we know …” he said in the university’s news release. “Maybe it will go away quickly and we won’t talk about it anymore, but if it persists for a third year, then we’ll know something really unusual is going on.”