If only the rocks could talk.

If only the sandstones could sing, imagine the stories they’d tell, of dinosaurs, mammoth hunters and the “ancient ones” known as the Anasazi.

All roamed southern Utah over the eons, long before Native Americans struggled to hold their land against Mormon settlers, modern life and now, Donald Trump.

As the President arrives in Utah Monday afternoon, this rocky corner of the Wild West is a battlefield once again, but this time the warriors will carry briefcases and lawsuits.

During a speech in Salt Lake City, Trump is expected to announce the fate of two national monuments: Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante, created by Democratic predecessors to protect culture, history and natural beauty.

He is expected to shrink both significantly, much to the delight of locals who see them as nothing more than a 3-million-acre federal land grab. The drillers, miners and frackers who were shut out by Bill Clinton and Barack Obama’s use of the Antiquities Act would have new leases on life. Orrin Hatch and his fellow Utah Republicans would have a major victory to celebrate.

But those who believe the rocks can talk, through countless fossils, sacred ruins and desert solitude, are bracing for a fight.

“I’m going to sue him,” says Yvon Chouinard, founder and CEO of outdoor gear maker Patagonia. “It seems the only thing this administration understands is lawsuits. I think it’s a shame that only 4% of American lands are national parks. Costa Rica’s got 10%. Chile will now have way more parks than we have. We need more, not less. This government is evil and I’m not going to sit back and let evil win.”

Chouinard led the effort to move a major outdoor show from Salt Lake City to Denver in protest of Utah’s land use politics and he’s been a big supporter of the historic coalition of the five local tribes, which put aside ancient rivalries and lobbied for monument protection.

But his arguments carry no sway at a pro-Trump, anti-monument rally in Monticello. Here, Chouinard represents all the liberal interests from outside, conspiring to pit neighbor against neighbor. “What’s his net worth? One billion dollars? Two billion?” says San Juan County Commissioner Phil Lyman. “You got Patagonia in here waving the flag of environmentalism while he’s completely exploiting the outdoors for industrialized tourism. For a person in that position to try and lecture morality to one of the poorest counties in the entire nation is wrong.”

The size of New Jersey, San Juan is the biggest and poorest county in Utah and with this moment of political victory, Lyman finds kinship with the coal miners of Appalachia.

He points out that Bears Ears is the fifth national park or monument in his county and argues that oil and gas extraction would have less impact on the landscape than the brand of adventure tourism that has transformed nearby Moab. “By designating a monument, you are using a tool that will bring hordes of people to a place that is very sensitive,” he says.

But according to former county commissioner and Navajo elder Mark Maryboy, cultural sensitivity is hard to find in San Juan County. “They didn’t want to work with us,” he says. “In fact, one of the county commissioners told me ‘You guys lost the war so you have no business talking about the land planning process.'”

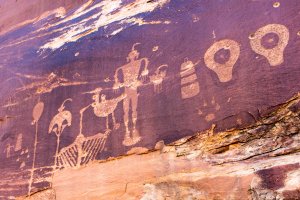

With efficient strides, he drops into a canyon near the San Juan River, past one of the 100,000 sacred ruins in Bears Ears, to a wall covered in 1,200-year old rock art. The spindly renderings of man and animal are the work of an artist they’ve dubbed “Wolfman” for the paw print signature that accompanies the pictoglyphs. And then he points out the modern bullet holes.

To his Navajo faith, this canyon holds the spirits of his loved ones and these carvings are just as sacred as any art in the Vatican or any wall in Jerusalem, yet someone has been using it for target practice.

“The local white community members are determined to get rid of all the art rock,” he says. “It stands in the way of progress for them. It stands in the way of a job. New cars. New clothes. Rolex watch.”

He’s heard the argument that his people need jobs and that the extraction industry could provide them while protecting the most important sites.

But, he feels, history hasn’t shown that to be true.

“The experience that Native Americans see in this county is discrimination,” he says. “They are the last ones to be hired for any position. Even if there’s a huge mining operation opening up, they will not be hired for that position. And they will be exposed to the toxic materials that are left on the ground or in the air.”

Regardless of Trump’s decision and unless Utah politicians can figure out a way to take them back and sell them off, the 3 million acres around Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante will remain public.

If you are an American, this is your land and these are your rocks. Pay them a visit sometime. You’ll be amazed at the stories they tell.