What’s the first thing you should worry about when you look at the packaging on your fast food or takeout?

No, it’s not Covid-19 — science assures us the risk of catching the novel coronavirus that way is miniscule.

Worry instead about the toxic chemicals coating the wrappers of your fast food burger or your molded-fiber container full of salad or veggies, says a new report by environmental advocacy groups Toxic-Free Future and Mind the Store.It’s a campaign run by Safer Chemicals, Healthy Families to encourage manufacturers to avoid toxic chemicals in products.

The report, entitled “Packaged in Pollution: Are food chains using PFAS in packaging?,” was released Thursday.

Testing by the groups revealed toxic PFAS substances — man-made perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl chemicals — in the food packaging of Burger King’s “Whopper,” chicken nuggets and cookies; in Wendy’s paper bags; and in McDonald’s wrappers for the “Big Mac,” french fries and cookies.

“As the largest fast-food chain in the world, McDonald’s has a responsibility to its customers to keep them safe. These dangerous chemicals don’t belong in its food packaging. I, for one, am NOT ‘lovin’ it,'” said Mike Schade, Mind the Store campaign director, in a statement.

In addition, so-called “environmentally friendly” molded fiber bowls and containers sold by the Mediterranean culinary chain Cava, the Canadian restaurant franchise Freshii and fast-casual salad chain Sweetgreen tested extremely high for PFAS, according to the report.

In fact, paper-fiber containers showed the highest levels of any packaging tested.

“Ecologically friendly doesn’t mean human health friendly. Those are two different considerations,” said Dr. Leonardo Trasande, chief of environmental pediatrics at NYU Langone, who was not involved in the study. “This example in the report really brings that home.”

However, not all of the tested wrappings contained these dangerous chemicals. Paperboard cartons or clamshells for French fries, potato tots and fried chicken pieces sold at the three burger chains all tested below the screening level, the report found.

“This is a very clear demonstration that chemicals that are present in our food packaging don’t have to be,” said microbiologist Linda Birnbaum, the former director of the National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences and the National Toxicology Program.

“In other words, you can make things that don’t have to have this stuff in it,” said Birnbaum, who was not involved in the report.

Today, Cava announced it will eliminate PFAS from its food packaging by mid-2021; Sweetgreen announced in March it would eliminate the chemicals by the end of the year. Freshii told CNN that it was transitioning to two sizes of PFAS-free pulp bowls by early 2021.

McDonald’s Corporation sent the following statement: “We’ve eliminated significant subset classes of PFASs from McDonald’s food packaging across the world. We know there is more progress to be made across the industry and we are exploring opportunities with our supplier partners to go further.”

CNN reached out to the other two companies but did not receive a response before our publication deadline.

What are PFAS?

The PFAS chemicals are made up of a chain of linked carbon and fluorine atoms, which do not degrade in the environment.

“In fact, scientists are unable to estimate an environmental half-life for PFAS, which is the amount of time it takes 50% of the chemical to disappear,” according to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

While two of the most ubiquitous PFAS — the 8-carbon chain perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) — were removed from consumer products in the US in the early 2000s, the industry has spawned many more: More than 4,700 types of PFAS existed in 2018, a number that rises as industry invents new forms.

PFAS chemicals are used in all sorts of products we purchase: Nonstick cookware, infection-resistant surgical gowns and drapes, cell phones, semi-conductors, commercial aircraft and low-emissions vehicles.

The chemicals are also used to make carpeting, clothing, furniture and food packaging resistant to stains, water and grease damage. Foods which contain a lot of grease — such as burgers, fries and cookies — are prime candidates for wrappers made with PFAS.

“Maybe that’s something that we all as consumers need to think about,” Birnbaum said. “Is it more important to have PFAS wrappings on our food to prevent grease soaking through? Or do we just accept that as something that we deal with?”

The PFAS chemicals in food wrappers and containers are part of the newer generation, made with 4- or 6-carbon chains to replace the rejected 8-chain PFOA and PFOS versions.

However, newer forms appear to have many of the dangerous health effects as the older versions, say experts, leaving consumers and the environment still at risk.

“So they went to the shorter chain carbons, and you study them, and they do just about the same thing,” Birnbaum said. “Why would we think that you can make a very minor change in a molecule you are manufacturing and the body wouldn’t react in the same way?

Studies also show the newer PFAS chemicals may migrate into food more readily than older forms.

“This is a whole pattern of what has been happening,” Birnbaum added. “Some people call it the ‘Wack-a-Mole’ problem, others call it the chemical conveyor belt. We don’t really require adequate safety testing before things are put on the market.”

It’s also hard to keep track of the substances in “the chemical Whack-a-Mole,” Trasande added.

“It’s not to say that there aren’t others down the pike that may have the same kind of problems,” he said. “Because we innovate our chemical structures and that may help get past the US Food and Drug Administration regulatory loophole and get usability for food contact.”

Health dangers of PFAS

There is extensive evidence of the harm PFAS substances can do to the body, as well as to the environment. Research over the last decade has found exposure to PFAS to be associated with liver damage, immune disorders, cancer and endocrine disruption — meaning they mimic or interfere with the body’s natural hormone processes.

Endocrine disruptors — such as the infamous pesticides DDT and dioxin, plastic additives Bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates — join PFAS chemicals in being linked with developmental, reproductive, brain, immune and other problems, according to the National Institute of Environmental Sciences.

A major review, published in the Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology journal last month, lists studies linking endocrine-disrupting chemicals with semen damage and prostate cancer in men, breast cancer, polycystic ovarian syndrome and endometriosis in women, child and adult obesity and more.

PFAS have been detected in the blood of 97% of Americans, one 2015 report by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found.

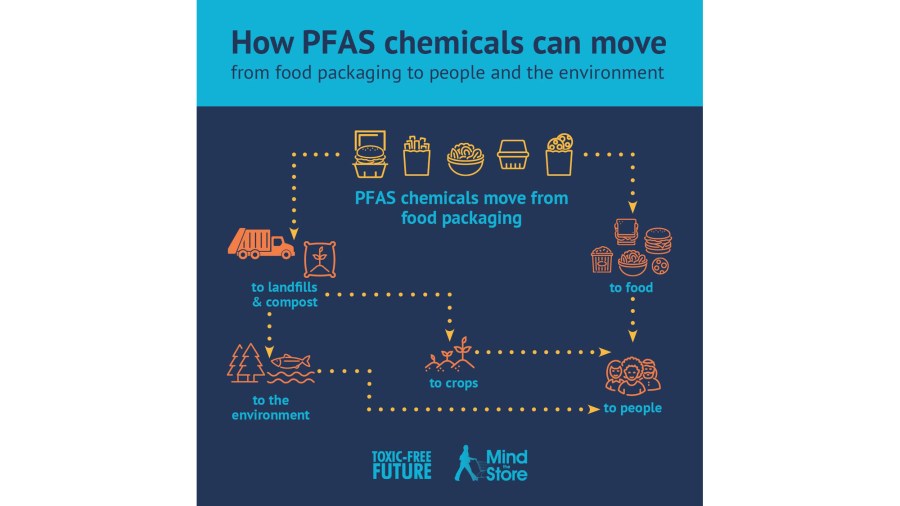

The packaging continues to damage the environment and human health after its been discarded, contaminating drinking water, food and air. Even if a person avoids PFAS in their own home, evidence shows that these chemicals still enter the environment, experts say, where they can make their way back to people.

Many more examples

This is not the first report to find such chemicals in our food packaging.

A 2017 study examined 400 samples of food wrappers, paperboard containers and beverage containers from fast food restaurants throughout the United States. Paper cups had no contamination, but 56% of dessert and bread wrappers, 38% of sandwich and burger wrappers and 20% of paperboard wrappers (the type used to hold french fries, for example) contained detectable levels of PFAS chemicals.

Over a third of the samples tested at levels far above what is considered to be acceptable, the study found.

In late 2018, Safer Chemicals Healthy Families and Toxic-Free Future released a report entitled “Take Out Toxics: PFAS Chemicals in Food Packaging,” in which they found evidence of PFAS chemicals in nearly two-thirds of takeout containers made of paper, like those used at self-serve salad buffets and hot bars.

In response, Whole Foods became the first grocery chain in North America to publicly commit to remove PFAS from take-out containers and deli and bakery paper. Other brands, such as Trader Joe’s, Panera Bread and Ahold Delhaize have made advances, but Mind the Store’s latest retail ranking still gives 18 retailers an “F,” including giants Burger King, McDonald’s, Popeyes, Publix, Starbucks and Subway.

“The biggest reason why it’s been slow going is not a lack of effort by these non-profit organizations, or a lack of concern by consumers, but because there is no requirement by the FDA to systematically test these products,” Trasande said.

“They come to market without the kind of toxicology testing and pre-market testing for safety that we truly need.”

Vote with pocketbook

What’s to be done? As it turns out, consumers have a lot of clout when it comes to voting with their pocketbooks.

“When the consumer pushes back, it makes a difference,” Birnbaum said. “For example, Home Depot announced last year they were no longer going to sell stain-resistant carpeting because they were getting push back from buyers.”

“The same happened with flame retardants in mattresses, about 10 or 15 years ago, when people said I don’t want to find flame retardant in my mattress,” she added. “And the reason the FDA finally banned BPA from baby bottles and sippy cups was because new mothers were saying, ‘I don’t want BPA near my baby,’ and refusing to buy things with it.”

Trasande agrees: “The few data that have been published have driven relatively rapid change. I remember when one of the reports came out about two supermarket chains with their buffet-style food packaging. And literally weeks later on Instagram and Facebook, they announced they had swapped out their materials for PFAS-free.

“We know that companies respond to consumer concerns because they’re tied to profit margin and market share,” Trasande said.

States have been on the front line of pushing for change. The states of Washington and Maine, and the cities of Berkley and San Francisco banned PFAS in paper food packaging a few years ago. New York is in the process of banning it this year. Two Congressional representatives introduced the Keep Food Containers Safe from PFAS Act last year, but no action has been taken.

Last week the FDA announced a voluntary agreement with three paper manufacturers, saying they will start phasing out some synthetic chemicals used in food packaging materials over the next three to five years. The FDA also noted that in 2019 a fourth manufacturer stopped their sales of certain PFAS products in the US market.

These moves come on the heels of an FDA analysis from earlier this year that found certain PFAS chemicals used in food packaging could be found in drinking water and one last year finding the chemicals were persistent in human diets.

More needs to be done, say experts, which requires educating the public on the dangers of PFAS chemicals to both human health and the environment.

“I don’t think people want necessarily chemicals in their food that are going to get into their body and maybe cause health effects or last a long, long time in the environment,” Birnbaum said. “But I don’t think people know that.”