Frustrated with the University of North Carolina’s handling of sexual violence reports, five women took matters into their own hands in 2013 by going public with their stories and pursuing justice through other means.

Sound familiar? Maybe to those following the story of Delaney Robinson this week. The UNC Chapel Hill sophomore went public with allegations that the school failed to conduct a thorough investigation when she accused a football player of raping her on Valentine’s Day.

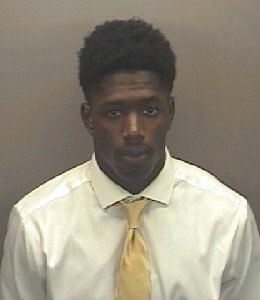

The allegations came to light after Robinson reported them to an Orange County magistrate in an effort to bring charges against the athlete, Allen Artis. Artis faces misdemeanor charges, and a criminal investigation continues to determine if felony charges are merited.

Like many schools across the country, UNC at Chapel Hill is grappling with how to deal with sexual misconduct on campus. What’s troubling to some alumni and advocacy groups about this instance is its timing, three years after the women turned their allegations into a civil rights case and two years after the school revised its misconduct policy to address some of the problems Robinson and her attorney now describe.

The school declined to comment on Robinson’s allegations, citing student privacy laws. In an open letter to the UNC Chapel Hill community, Chancellor Carol Folt cautioned against rushing to conclusions. She stood by university employees and urged the public to have faith in the adjudication process.

“The issues involved in sexual assault are challenging. Inevitably, some will walk away from the process disagreeing with the outcome. That does not reflect in any way on the integrity of our employees or our process,” Folt said.

“We are committed to ensuring every step of our policy and procedures is correctly followed. Sometimes, to get it right takes longer than anticipated. But in the end, a respectful, reliable and equitable investigation must be the result.”

A new policy

After a yearlong review by a campus task force, the revised policy is among the most thorough in the country, said former UNC student Andrea Pino, co-author of “We Believe You: Survivors of Campus Sexual Assault Speak Out.” Pino was one of the five women who went public and filed complaints against UNC in 2013 with the US Department of Education. She also appeared in the CNN documentary about campus sexual assault, “The Hunting Ground.”

Among the most significant changes were expanded definitions of consent and incapacitation, an expanded scope of prohibited behavior, and streamlined reporting options that are easy to find on the school’s website.

The school shifted jurisdiction over the cases from a student-led panel to a Title IX compliance coordinator in the school’s Equal Opportunity and Compliance Office. UNC added counseling services in the interest of providing care and ensuring the safety of the reporting party and the campus community.

“These individuals and staff within these offices are well trained on how to conduct investigations, document incidents, and respond to reports,” the policy states.

The policy changes were intended “to add resources to provide compassionate care and accommodations for those who need support with their day-to-day logistics,” Folt said in her open letter.

Since the changes took effect in 2014, the school has experienced a 52% increase from the previous year in formal investigations of sexual assault in what Folt called a positive sign that “community members feel more comfortable coming forward.”

An annual report for the 2014-2015 academic year breaks down outcomes in allegations of interpersonal violence, sex discrimination, sexual Assault, sexual harassment or stalking involving students. Of 18 allegations, 11 resulted in unspecified sanctions, and seven did not.

The problem is enforcement, Pino said, as Robinson’s case apparently suggests.

“To this day I’m not sure if anyone has been expelled for sexual assault,” she said. “As great as your policy is, if it’s not leading to deterrence, then it might as well not be there at all.”

‘Suspicion and condemnation’

Like Pino and her co-complainants, Robinson says the school failed to take her report seriously, subjected her to humiliating questions and treatment, and dragged out the process beyond a reasonable time frame.

According to the policy, the goal is to resolve all reports within one academic semester, which includes up to 35 business days for the investigation and 25 days for rendering a decision and finalizing an outcome, if necessary. A case could take longer, depending on its “complexity,” to ensure its “integrity and completeness.”

Robinson, who filed a report March 9, is still awaiting a decision. School officials told her the investigation would conclude by April 26, with a conclusion within 90 days of filing. She blames the delays on “countless errors and missteps” in an “ineffective investigation” by UNC’s Department of Public Safety from the moment she went to the hospital for a rape kit. A letter from her attorney to the chancellor said the lead investigator inexplicably waited one month to send the kit to the state crime lab for testing despite best practices for evidence handling and against the interest of processing the case in a timely fashion.

Robinson says Department of Public Safety investigators asked questions about what she wore that night, how much she drank and how many men she had slept with before. Her attorney, Denise Branch, said in the letter to the chancellor that investigators proposed alternative hypotheses for why she reported the rape: She regretted the consensual encounter; she wanted to claim she had sex with a UNC athlete; she was upset he didn’t ask for her number.

The treatment “is in stark contrast to the University’s promise of protection and support,” Branch wrote. Instead, Robinson was treated with “suspicion and condemnation.”

With her accuser, the investigators displayed “camaraderie,” telling him not to “sweat it” and to keep playing football. An investigator asked if he’d gotten other girls’ phone numbers that night and told him to “rock on” when he responded yes, according to audio recordings Branch and Robinson say they reviewed.

Such questions appear at odds with the school’s promise of a “well trained” staff versed in the policy’s definitions of consent, intoxication and sexual conduct, as well how to conduct an investigation.

The policy defines consent as an affirmative, conscious and freely made decision, conveying a “clear willingness” through “understandable words or actions.”

Silence, passivity, lack of resistance or a previous relationship or encounter do not imply consent. A person who is incapacitated by alcohol or drugs cannot consent. No matter the level of intoxication, if a person has not “affirmatively agreed to engage in sexual contact, there is no consent.”

As for the accused, intoxication “is never an excuse for or a defense,” and “it does not diminish one’s responsibility to obtain consent.”

Fed up with waiting, Robinson availed herself of the option under North Carolina law to go before a magistrate and swear to the allegations against Artis, a linebacker for North Carolina’s football team. Artis was released on bond. Neither he nor his attorney have responded to CNN’s requests for comment.

Awaiting a conclusion

As for Pino and the other women, they turned their grievances into a civil rights case by filing a complaint with the US Department of Education, alleging violations of Title IX, a provision of the Education Act that prohibits gender-based discrimination or violence in schools that receive federal funding. They also filed a Clery Act complaint, alleging that the school failed to disclose crime statistics to the campus community.

Like Robinson’s, their case is still pending.

And what does Robinson want, exactly? Expulsion, felony charges for Artis?

“I just want it to be completed,” she said.