Fidel Castro, the Cuban despot who famously proclaimed after his arrest in a failed coup attempt that history would absolve him, has died at age 90.

Castro’s brother and the nation’s President, Raul, announced his death Friday on Cuban TV.

At the end, an elderly and infirm Fidel Castro was a whisper of the Marxist firebrand whose iron will and passionate determination bent the arc of destiny.

“There are few individuals in the 20th century who had a more profound impact on a single country than Fidel Castro had in Cuba,” Robert Pastor, a former national security adviser for President Jimmy Carter in the 1970s, told CNN in 2012.

“He reshaped Cuba in his image, for both bad and good,” said Pastor, who died in 2014.

Castro lived long enough to see a historic thaw in relations between Cuba and the United States. The two nations re-established diplomatic relations in July 2015, and President Barack Obama visited the island this year.

President Raul Castro — who took over from his ailing brother more than eight years ago — announced that breakthrough to the nation but observers noted Fidel’s silence on the matter.

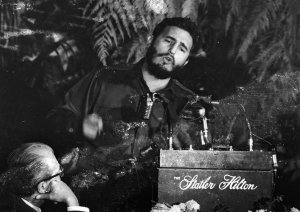

Castro’s stage was a small island nation 90 miles from the United States, but he commanded worldwide attention.

“He was a historic figure way out of proportion to the national base in which he operated,” said noted Cuba scholar Louis A. Perez Jr., author of more than 10 books on the Caribbean island and its history.

“Cuba hadn’t counted for much in the scale of politics and history until Castro,” said Wayne Smith, the top US diplomat in Cuba from 1979 to 1982.

Castro became famous enough that he could be identified by only one name. A mention of “Fidel” left little doubt who was being talked about.

Castro and the road to power

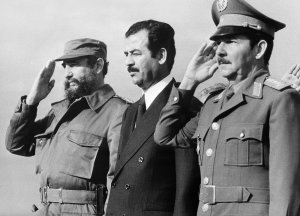

It was a bearded 32-year-old Castro and a small band of rough-looking revolutionaries who overthrew an unpopular dictator in 1959 and rode their jeeps and tanks into Havana, the nation’s capital.

They were met by thousands upon thousands of Cubans fed up with the brutal dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista and who believed in Castro’s promise of democracy and an end to repression.

That promise would soon be betrayed, though, and Castro held on to power for 47 years until an intestinal illness that required several surgeries forced him to relinquish his duties temporarily to younger brother Raul in July 2006. Castro resigned as president in February 2008, and Raul took over permanently.

One Castro or another has ruled Cuba over a period that spans almost 60 years and 11 US presidents. Fidel Castro outlived six of those presidents, including Cold War warriors John F. Kennedy, Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan.

At the height of the Cold War, Castro used a blend of charisma and repression to install the first and only communist government in the Western Hemisphere, less than 100 miles from the United States.

Cuba and the Soviet Union established diplomatic relations on May 8, 1960, further eroding the relationship with the United States. Castro, who had long blamed many of Cuba’s ills on American influence and resented the US role in hemispheric politics, quickly intensified cooperation with the Soviet Union, which began sending large subsidies.

“Fidel Castro came to power with a conviction that he was going to have a major revolution in Cuba, that he was going to stay in power indefinitely, that he was going to fight American imperialism and that he needed a ‘daddy’ and his ‘daddy’ was the Soviet Union,” said Jaime Suchlicki, director of the Institute for Cuban and Cuban-American Studies at the University of Miami.

‘Taunted, antagonized and irritated’

In doing so, Castro defied a hostile US policy that sought to topple him with a punishing trade embargo that started in 1962 and continued for the rest of his life.

“He taunted, antagonized and irritated the United States for more than a half century,” said Dan Erikson, a senior adviser for Western Hemisphere affairs at the US State Department and author of “The Cuba Wars: Fidel Castro, the United States and the Next Revolution.”

Castro also survived numerous assassination attempts by the CIA and anti-Castro exiles in the early 1960s. He took delight in pointing out how none of them succeeded, not even the plot that called for explosives to be placed in the ubiquitous cigars he later would quit smoking for health reasons.

“I have never been afraid of death,” Castro said in 2002. “I have never been concerned about death.”

Until his last breath, Castro held tightly to his belief in a socialist economic model and one-party Communist rule, even after the Soviet Union disintegrated and most of the rest of the world concluded state socialism was an idea whose time had passed.

“The most vulnerable part of his persona as a politician is precisely his continued defense of a totalitarian model that is the main cause of the hardships, the misery and the unhappiness of the Cuban people,” said Elizardo Sanchez, a human rights advocate and critic of the Castro regime.

But Castro’s defenders in Cuba point to what they see as social progress, including racial integration, universal education and health care. Instead of blaming an inept socialist system, they fault the US embargo for the country’s economic woes.

“What Fidel achieved in the social order of this country has not been achieved by any poor nation, and even by many rich countries, despite being submitted to enormous pressures,” said Jose Ramon Fernandez, a former Cuban vice president.

Cuban exiles

Castro’s political staying power was a source of puzzling consternation and bitter frustration for Cuban exiles, who never imagined he would rule so long.

“We came here with a round-trip ticket … because we thought the revolution was going to last days,” said US Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, who arrived in Florida as a child and later became the first Cuban-American elected to Congress. “And the days turned into weeks, and the weeks to months, and the months to years.”

Castro occasionally allowed disenchanted Cubans to leave, with most going to the United States. More than 260,000 Cubans left in a US-organized airlift between 1965 and 1973. In 1980, Castro let another 125,000 leave in the chaotic Mariel boatlift. Among them were criminals released from Cuban jails who brought a violent crime wave to Florida.

At other times, desperate Cubans fled the island nation in makeshift boats across the treacherous Straits of Florida. Thousands died from drowning or exposure to the brutal Caribbean sun.

The center of the exile community is Miami, where the Cuban American National Foundation became a powerful lobbying group courted by US politicians. For decades, pressure and political donations from the exile community have thwarted any efforts to lift the embargo.

The early years

Castro was born August 13, 1926, in Oriente Province in eastern Cuba. His father, Angel, was a wealthy landowner originally from Spain. His mother, Lina, had been a maid to Angel’s first wife.

Educated in private Jesuit schools, Castro went on to earn a law degree from the University of Havana in 1950 and became a practicing attorney, offering free legal services to the poor.

In 1952, at the age of 25, he ran for the Cuban congress. But just before the election, the government was overthrown by Batista, who established the dictatorship that put Castro on the road to revolution.

On July 26, 1953, Castro led a group of about 150 rebels who attacked the Moncada military barracks in Santiago in an unsuccessful attempt to overthrow Batista. Most of the attackers were killed. Castro and a handful of others were captured.

The attack made him famous throughout Cuba, but it also earned him a 15-year prison sentence.

At his sentencing, Castro told the court, “Condemn me, it doesn’t matter. History will absolve me.”

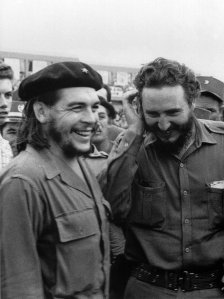

He was released in 1955 as part of an amnesty for political prisoners and lived in exile in the United States and Mexico, where he organized a guerrilla group with brother Raul and Ernesto “Che” Guevara, an Argentine doctor-turned-revolutionary. They named themselves the July 26 Movement, after the date of the failed Moncada attack.

In 1956, Castro and a few dozen rebels headed for Cuba aboard an old yacht called the Granma. Off course and long overdue, they beached the craft off the coast of Oriente Province.

Batista’s soldiers were waiting for them, and, again, most of Castro’s followers were killed.

The Castro brothers, Guevara and a handful of other survivors fled into the Sierra Maestra mountains along the nation’s southeastern coast, where they waged their guerrilla campaign against Batista.

Relations quickly fell apart

While the United States quickly recognized the new government when Castro came to power on January 1, 1959, tensions arose after Cuba began nationalizing factories and plantations owned by American companies. In January 1961, Washington broke off diplomatic relations.

Less than four months later, a group of CIA-trained Cuban exiles, armed with US weapons, landed at the Bay of Pigs in Cuba in an attempt to overthrow Castro. The invasion failed miserably, with many of the exile fighters killed or captured.

The United States later paid $53 million worth of food and medicine in exchange for more than 1,100 prisoners.

Two weeks after the Bay of Pigs, Castro formally declared Cuba a socialist state.

In October 1962, the United States and the Soviet Union came to the brink of nuclear war over Soviet nuclear missiles installed in Cuba. President John F. Kennedy demanded that the Soviets remove the weapons, and he established a naval blockade around the island. In the end, the Soviet Union backed down and removed the missiles.

Cuba, which had struggled economically despite the Soviet subsidies, underwent even more severe hardships starting in 1991 after the collapse of the Soviet Union. By some accounts, imports and exports dropped by 80%, and the gross domestic product, a measure of the goods and services the nation produced, fell by more than 30%. This Special Period in Time of Peace, as the Cubans called it, lasted through the decade, and Cuba continued to struggle well into the 21st century.

A private life kept private

Not much is known about Castro’s private life, which he guarded steadfastly.

Before he came to power, Castro married Mirta Diaz-Balart, the daughter of an established and politically connected Cuban family, in 1948. They had a son the next year and named him Fidel.

His wife filed for divorce in 1954 and won custody of young Fidelito, as he was known.

Castro is reported to have fathered 10 children with six women. His second wife, Dalia Soto del Valle, is the mother of five of his eight sons. Seven of his 10 children have names that begin with the letter A.

Toward the end of his life, Castro grew visibly weaker, spurring speculation about his health. He fainted while speaking at a rally in June 2001 and injured himself when he fell after a speech in late 2004.

He remained mostly out of sight after falling ill in 2006 but returned to the public light in the summer of 2010, making a series of appearances and even giving a short speech to a special session of the National Assembly that he convened. In January 2014, photos showed a frail and hollow-eyed Castro hunched over a cane and supported by an aide as he toured an art studio opening in Havana.

A divisive figure in life, Castro will likely remain so for many years after his passing.

“The legacy of Fidel Castro will not really be known until 50 years after his death,” said Cuba scholar Perez.

Ann Louise Bardach, author of the 2009 book “Without Fidel: A Death Foretold in Miami, Havana, and Washington,” spent more than two decades following and writing about the Castros and Cuban politics.

“The possible aspects of his legacy,” she said, “will likely be nationalism, a sense of Cuban identity — of ‘cubanidad.’ But at a price far too steep that will leave a debt for generations to come.”

Erikson, the State Department official, noted Castro’s shortcomings.

“He really was the main proponent of the Cuban Revolution,” Erikson said, “but he failed to deliver on his promises.”

Assessing a mixed legacy

Castro clearly left behind a different Cuba, many observers say, but not necessarily a better one.

“You could say that one positive legacy is that there are a lot of educated Cubans,” said Adriana Bosch, a Cuban-born filmmaker who lives in the United States and produced a documentary on Castro for PBS. “But if you don’t create the economic conditions where those people can work and make contributions, what you have is a bunch of educated waiters and waitresses, which is what you have in Cuba now.”

The enduring legacy, Castro’s critics say, is a society in disarray.

“Cuba is a country divided, a country where you have 2 million people in exile, a country that is economically wrecked, a country that is ecologically wrecked, a country that is probably without a lot of civic values, and a country that is facing a very uncertain future,” Bosch said.

“Many of the decisions that have been taken by the leadership and by Fidel Castro were not necessarily the decisions that were best for the revolution, but were decisions geared to keeping him in power,” Lisandro Perez, a Cuba expert at Florida International University, told CNN.

In the end, Castro’s declaration decades ago that history would issue the final verdict was accurate. Time will tell, but at the end of his long life, it appeared he would not be absolved.