Work has officially begun on a bullet train to connect Southern California with Las Vegas, bringing the number of active high-speed rail projects in California to two.

The groundbreaking of Brightline West took place April 22, just months after the endeavor was awarded billions from the federal government to get the project off the ground.

In December, the Biden Administration began releasing billions in federal grant funding to passenger rail projects across the country, including earmarking more than $6 billion for the two ambitious projects currently underway in California.

The California High-Speed Rail Authority was awarded a historic $3.07 billion in grant funding from the Biden Administration for its state-spanning rail system, while Brightline West was chosen to receive around $3 billion for its SoCal-to-Las Vegas bullet train.

Both projects aim to transport passengers to their destination at high speeds from the comfort of electric-powered trains while providing thousands of union jobs during construction. But their similarities mostly end there.

So what’s the difference between the California High-Speed Rail and Brightline West?

First and foremost: scale.

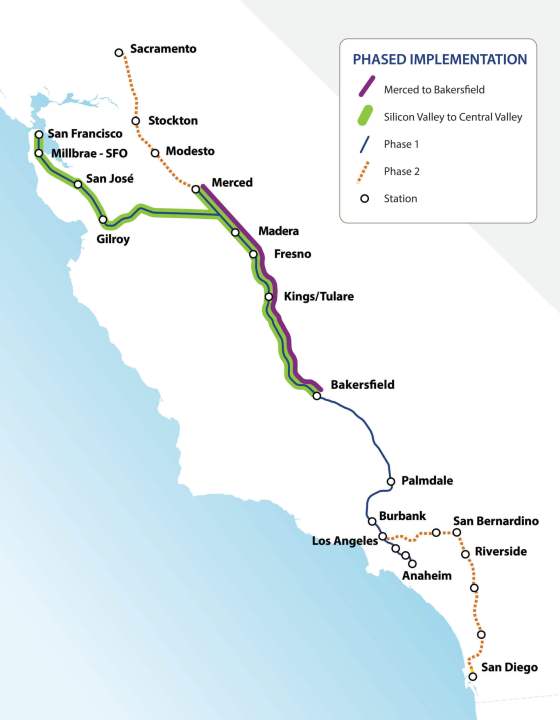

The California High-Speed Rail project, aka CAHSR, is the most ambitious public works project in California since the interstate and freeway system was built. The system, in its final form, if it ever becomes a reality, will transport passengers from as far north as Sacramento to as far south as San Diego. But it’s probably best known for being billed as the connector between Los Angeles and the Bay Area.

The CAHSR will be opened in segments. The first, known simply as the “initial operating segment,” will be located in the Central Valley, connecting the community of Merced to the city of Bakersfield some 170 miles south. Construction on that portion of the system is already well underway and it could begin operation as soon as 2030.

After that, construction will focus on coming through with the promise of L.A. to San Francisco in what’s been referred to as “Phase 1.”

That segment is more than 500 miles and will include some of the largest man-made tunnels ever constructed in both Northern and Southern California. That portion of the project will trail behind the initial operating segment by several years.

The additional legs, including Sacramento to San Diego, will represent the “complete” system. That extension of the project is still significantly more than a decade away and officials say much of that planning will need to be redone for the modern day before an exact timeline can be determined.

Meanwhile, the Brightline West project is a relatively straight shot, 218 miles between the Inland Empire and Las Vegas. About 80% of the system will reside in California, following along Interstate 15 between Vegas and Rancho Cucamonga.

That system could be up and running by as early as 2028, officials said, possibly in time for the Summer Olympics in Los Angeles.

Speaking of Interstate 15, another key difference between CAHSR and Brightline is what’s called “right of way,” and it’s possibly the biggest hurdle (aside from funding) these types of projects encounter. A right of way literally means that the train has permission to operate in the area.

The SoCal-to-Vegas bullet train benefits from a relatively uncomplicated right of way. The train will operate alongside Interstate 15 and usage agreements to grant the train permission to operate in that space were established years ago.

Meanwhile, the California High-Speed Rail has the challenge of having to deal with multiple owners of various rights of way. Different cities, counties, freight companies and power companies all have individual property rights and points of interest along the system’s proposed track. The Authority is required to purchase or negotiate the use of these rights of way before any tracks can be laid. That process can be both time-consuming and costly, making it one of the major reasons for the project’s slow development and ballooning price tag.

And on the topic of costs, the single-biggest difference between the two projects is the method for funding.

The California High-Speed Rail is a public endeavor, funded by taxpayers at the state level, with some support from the federal government. The complete system will cost tens of billions of dollars and only a portion of the funding has been acquired so far, but the CAHSR Authority is in constant search of additional funds to make the entire project a reality.

The project has the added costs of needing to build bridges and other structures to keep vehicle and pedestrian traffic from coming into the path of the trains, in addition to the required construction of several new dedicated train stations along its path.

December’s grant from the Biden administration all but ensures that the Merced to Bakersfield portion of the system will be completed and will begin operation in the coming years.

On the other hand, Brightline West is a private company, and despite receiving major help and cash from the federal government, it plans to find the rest of the required funding for the project on its own.

In January, Brightline received a $2.5 billion injection in the form of private activity bonds issued from the U.S. Department of Transportation, which it will eventually have to pay back.

The $3 billion grant the company received from the federal government in December, plus the new funding from those bonds, is enough to get the project off the ground, but the company will have to obtain financing for the rest of the construction.

The current estimated price tag is around $12 billion and Brightline previously committed to contributing $10 billion to the project, which includes the construction of its own stations along the path, including a new state-of-the-art transit center in Rancho Cucamonga that will be adjacent to an existing Metrolink station.

Despite their differences, and a nationwide conversation about the best and most-effective method for revolutionizing America’s transportation industry, the projects are being built with effective communication and cooperation between them, officials said.

The two groups have even discussed setting up a connection in the Palmdale area, Brightline says.

Both projects have received bipartisan support at the state level and federal backing by President Joe Biden, who is known for his affinity for passenger rail service.

Biden has been critical of the country’s lagging infrastructure, including rail service, which he’s said has paled in comparison to other developed nations.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom has lobbied the president for support of the state’s high-speed rail projects.

In October 2023, Newsom took a trip to China to discuss clean energy and climate change initiatives, but he also had the opportunity to ride on the country’s high-speed rail system, which spans more than 26,000 miles and was built in a fraction of the time it has taken the American system to get off the ground.

Following the trip, Newsom wrote a letter to the president, thanking him for his continued support of California’s clean energy initiatives and urging him to approve the California High-Speed Rail’s grant application to allow for the initial operating segment to open as planned.

In December, following the news of the two projects getting big federal cash boosts, Newsom released a statement in which he promoted California as the epicenter for progress in the industry.

“California is delivering on the first 220-mph, electric high-speed rail project in the nation,” Newsom said. “This show of support from the Biden-Harris Administration is a vote of confidence in today’s vision and comes at a critical turning point, providing the project new momentum.”