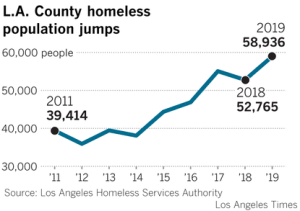

The number of homeless people counted across Los Angeles County jumped 12% over the past year to nearly 59,000, with more young and old residents and families on the streets, officials said Tuesday.

The majority of the homeless were found within the city of Los Angeles, which saw a 16% increase to 36,300, the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority said in presenting January’s annual count to the county Board of Supervisors.

The increase was registered a year after the previous tally found a slight decrease in the county’s homeless population.

The problem was apparent just outside the board meeting, where a man and a woman were camped out on a small patch of lawn. Tents regularly pop up on the pavement outside nearby City Hill and hundreds of people live in makeshift shanties that line entire blocks in the notorious neighborhood known as Skid Row.

The county’s Homeless Services Authority said it helped 21,631 people move into permanent housing during 2018 — a pace that would have helped rapidly end homelessness if economic pressures had not simultaneously pushed thousands more out of their homes.

But while some people who had been homeless managed to get permanent places to live, others who had homes were forced onto the streets of metro Los Angeles’ vast urban sprawl.

“People are being housed out of homelessness and falling into homelessness on a continuous basis,” said Peter Lynn, the authority’s executive director.

About a quarter of those counted became homeless for the first time in 2018, and about half of those cited economic hardship as the primary cause, the authority said.

To reduce homelessness, communities must overcome resistance to the placement of housing and shelters, officials said.

Three years ago, Los Angeles voters approved a tax hike and $1.2 billion housing bond to make a decade’s worth of massive investments to help solve the homeless crisis. That bond money has been committed to build more than half of the 10,000 new housing units planned countywide over the next decade, Lynn said.

About three-quarters of the homeless people counted were living outdoors, fueling concerns of a growing public health crisis with piles of garbage and rats near homeless encampments lining downtown sidewalks.

The Skid Row area is “ground zero” for the crisis, where the smell of human waste permeates the air and violence is common, said Estela Lopez of the Downtown Industrial Business Improvement District.

The district’s business members, mainly fish and produce vendors, pay additional property tax for on-demand power-washing of sidewalks and a private security force that mediates disputes and clears people congregating at companies’ front doors and loading docks.

“We’re not the police but we’re increasingly doing police work because we’re out there all day, every day,” said Lopez. “We’re the ones flagged down if someone has a seizure or if someone ODs.”

Lopez estimates her group’s private trash service removes between 5 and 7 tons of garbage every day.

County Supervisor Janice Hahn called the increase in homeless population “disheartening.”

“Even though our data shows we are housing more people than ever, it is hard to be optimistic when that progress is overwhelmed by the number of people falling into homelessness,” Hahn said.

The Los Angeles County figures mirror tallies across California, as state officials struggle to address a lack of affordable housing. In addition, officials said, wages among lower income people have not kept up with the rising cost of living.

Some state lawmakers on Tuesday called for legislation capping rent increases on some tenants and encouraging the construction of more affordable housing.

“We’re seeing folks who are working, have jobs and are homeless. They can’t afford the rent. They can’t afford to live in the communities in which they’ve grown up their entire life. And they’re being displaced,” said Assemblywoman Buffy Wicks, a Democrat from Oakland, where a countywide survey this year found a 43% increase in the homeless population over the last several years.

But California tenant legislation faces persistent opposition from landlords and other major housing bills have already sputtered this legislative session.

Officials in San Francisco, which struggles with income inequality and a growing number of homeless residents, are considering a proposal to force mentally ill and addicted people into treatment. Critics say the plan goes against the spirit of a city known for its fierce protection of civil rights.

The Los Angeles County count found a 24% increase in homeless youth, defined as people under 25, and a 7% jump in people 62 or older.

Officials estimate about 29% of people experiencing homelessness in the county are mentally ill or coping with substance abuse problems.

About two-thirds of all people on the streets of metro Los Angeles are male, just under one-third are female, and about 2% identify as transgender or gender non-conforming.